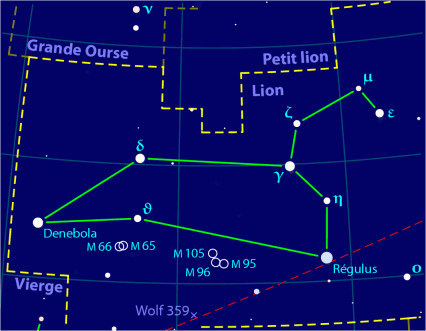

In the days of Ancient Mesopotamia, humans claimed to see a cat in the night sky.

Millennia later, members of modern human civilization still connect the disparate dots millions of miles away in recognition of that same cat: the constellation, Leo the Lion.

Terrestrially speaking, live Panthera leo prowl across African open planes and through dense brush landscapes. As a motif, the same sub-species has traversed traditions of assorted eras and areas. The lion is filmed roaring for MGM trademark footage, printed clawing across Bohemian coats of arms, and, ironically, encountered searching for its courage in classic narratives.

Humans have also typecast the courageous cat as a universal security guard for its shelters. Scowling bronze lions menacingly guard imperial Chinese palaces; monumental marble statues magnificently flank NYC cultural institutes. Chiseled lion visages grimace at passersby from the stone slabs that construct grandiose apartment buildings. On such facades, the muscular cat’s bestial behaviors threaten as its regal physique adorns.

But for as powerful as the lion sculptures seem, their power to protect carries a fundamental limitation: it is symbolic. The animals are inanimate, figurative facades in themselves—like how starry Leo’s existential state is really a bunch of big, burning gas balls far out in the universe.

But for as powerful as the lion sculptures seem, their power to protect carries a fundamental limitation: it is symbolic. The animals are inanimate, figurative facades in themselves—like how starry Leo’s existential state is really a bunch of big, burning gas balls far out in the universe.

Meanwhile in Hamtramck, Michigan, residents practice a more pragmatic means of employing felidae for protective purposes.

They use living breathing cats–of smaller sizes.

Lions may be the choice animal for the football team of the greater city that engulfs the city of Hamtramck. With Tigers, too, for baseball, it seems that Detroit has designated ferocious felines as its athletic juggernauts. But for home security, the domestic cat is suitable, size-wise. Two or three-story, freestanding urban homes of the American Midwest have no need for 600 pounds of cat.

Lions may be the choice animal for the football team of the greater city that engulfs the city of Hamtramck. With Tigers, too, for baseball, it seems that Detroit has designated ferocious felines as its athletic juggernauts. But for home security, the domestic cat is suitable, size-wise. Two or three-story, freestanding urban homes of the American Midwest have no need for 600 pounds of cat.

Others flourish in groups. Similar to the lionesses in prides, several mother cats congregate in clowders to raise their young and find ways to procure nourishment for their kittens, kith, and kin. Their tom counterparts? Perhaps off fending their turf–or marking it, or lazing upon it–like their lion cousins do.

Others flourish in groups. Similar to the lionesses in prides, several mother cats congregate in clowders to raise their young and find ways to procure nourishment for their kittens, kith, and kin. Their tom counterparts? Perhaps off fending their turf–or marking it, or lazing upon it–like their lion cousins do.

Whether the Hamtramck inhabitants intended it or not, their lion substitute is apt. In a 2010 study by the University of Edinburgh, researchers found that domestic cats and African lions exhibited a trio of similar personality traits: dominance, impulsiveness, and neuroticism.

Whether the Hamtramck inhabitants intended it or not, their lion substitute is apt. In a 2010 study by the University of Edinburgh, researchers found that domestic cats and African lions exhibited a trio of similar personality traits: dominance, impulsiveness, and neuroticism.

For defensive purposes, letting a dominant, impulsive, and neurotic lion pace in front of the home may sound like a smart protection strategy. Inside the home, well… those three virtues might make for some problematic behavior.

An five- or ten-pound creature acting in such a manner should probably be less destructive to indoor settings.

An five- or ten-pound creature acting in such a manner should probably be less destructive to indoor settings.

Inclusive of the interior and exterior environments of Hamtramck’s residential edifices, cats have traveled along countless trajectories throughout human history. Their domestication took place thousands of years ago, possibly around the rodent-fraught grain silos of what is now Egypt. Members of same ancient society considered cats to be a deity. One of their iconic relics still stands as the world’s largest monolith: the Sphinx of Giza. Although many uncertainties still surround the lion-man limestone statue–what the Ancient Egyptians called it, which Pharaoh built it, how the nose broke off its face–the colossus still shows us the deep roots of humankind’s fascination with felidae.

Should the foundations of contemporary civilization come tumbling down, it seems likely that we’ll have some four-legged friends to join us in the ongoing evolutionary journey.

Should the foundations of contemporary civilization come tumbling down, it seems likely that we’ll have some four-legged friends to join us in the ongoing evolutionary journey.

But until then, we can indulge in the sumptuous comforts that periods of peace offer…

But until then, we can indulge in the sumptuous comforts that periods of peace offer…